The Joy of Painting the Landscape, Chapter 4: (Diary, Notes from 2000-2022) On the Secrets for Greatness and Imitation!

My trials and errors have accrued to greater confidence with my art techniques, objective judgments and aesthetic sensitiveness. Of course, like the art of cooking, every one has his or her own recipe. Over the years, I have developed my own painting technique, which is not new, but it may bear the signature and fingerprints of my personality.

The truth is that the best artists would carefully write down their painting procedures with the cutting-edged rigor and punctiliousness of a doctor or lawyer of time-tested experiences.

This may explain why the best artists are, first and foremost, writers in their own right, for it is quite a daunting task to retain as much information and data without keeping records, diaries and carefully-dated materials of our painstaking trials and errors.

Great minds, such as Goethe, Alexander Von Humboldt, Leonardo da Vinci, A. Schopenhauer, Salvador Dali, Edward Gibbon, among the best thinkers of all times, owed their remarkable erudition to the accumulation of tomes of books: from the oldest literatures to the most wonderful books by contemporary authors.

Boxes upon boxes, drawers and closets are stuffed with manuscripts, scores of papers, carefully-numbered pages and writings, galore, may resume the long labors and toils of decades, which, after all, are the best trophies and harvest in the dusk of our lives.

Such books, if they are indeed great, may become part of our systematic approach to the complex problems and conundrums of existence. Like an artist, one is tasked to finding a little corner, a little studio, fire-proof, from which he-she may attempt to paint, either in words or ideas, the multicolored, multifarious canvas of our lives.

If such an artist is successful, then, he may then become a blessed child of beatitudes, the main problems of existence, ennui (boredom and sensual pleasures) would not beset him.

The Kingdom of God is Within You

Henry D. Thoreau, in the Walden Pond, assures us that he had never been bored. But if he such a person is only a great writer, such as Albert Camus, but not an artist, then the absurdity of existence would be the more glaringly obvious and unbearable, for he-she, lacking the blessed eyes of an artist, a saint, or a platonic philosopher, cannot rise to the realm of the divine and beautiful.

The higher spheres of Pythagoras are inaccesible for such a mortal, for he-she is neither intent on reaching the stars and skies of beauty, nor in enjoying the most spectacular landscapes and marvels as yet waiting for curious wanderers, wayfarers and pilgrims.

Such a person’s mind is bound to remain enchained with the shackles of things transient and fleeting. But for the artist, consecrated to his art with the devotion of a saint, life’s short span is not enough for all the great moments under the heaven of constant creativeness and productivity.

Of course, the art of living, vita beata, would demand a propitious hiatus from us, which the more intelligent ones, would gladly while-away in the nourishment of our intellectual faculties, or in the careful organization of our accumulated knowledge. For such a blessed human being, the avid reader, leisure is but a blissful moment with the higher pleasures of the mind: great books, prayers, meditation, classical music!

Foxed books beautifully saved in the shelves of yore are often the time-stricken records of sages and geniuses.

This is the main reason why I would compare an artist to a punctilious scribe, for like Leonardo da Vinci, who taught himself how to paint the subtlest secrets of light, shadow, tonality and color-application, one has to have an inner proclivity to being both a careful observer of all the phenomena of Mother Nature, a diligent writer, in equal terms, a marvelous scholar and an autodidact of great rigor and discipline without losing the freedom, fanciness and spontaneity of an artist.

True! For the most part, we own our improvement to the indispensable thoughts of great minds. Behind every artist there is always an inspiration, a master, and this is the golden secret behind greatness. Therefore, from the outset, choose the lives and biographies of the most excellent men and women.

Learn from their errors and mistakes, inquire on their trials and hardships, and from such failures and persecutions, go on to forge your inner-self anew, stronger and able to see clearly through the pervasive “gaslighting of your detractors.”

Overcome the World!

Like Christ, hold your wit firmly in what you already know to be part of your own experiences, part of your own treasure-trove, and when others try to cast doubts and questions in your talents, simply trust your silent inner scribe.

One cannot be too careful when spilling our thoughts through hasty writings or scribbles. A speedy hand is prone to err. May I find grace with those whose eyes and mind are but reflecting mirrors to superior works of arts and literature.

Most humbly, I felt compelled to correcting some petty trifles, lest my reader blame me of unwitting negligence and presumptuousness. Higher strivings may require the humility of a cobbler, or the long-wanderings of a pilgrim. But for a noble soul, be she or he a mere peasant or a prominent patrician, the things from above are always for the few (Check out Philippians Chapter 4:08)

But even if you are modest enough to seeking the simple things of this life, and would even build your cabin next to Thoreau, the noisy winds of the world and its vanities could rob you of the best moments and seasons.

Some would even cast doubts on your sanity, and may even declare you ripe for a madhouse. But here lies your strength, your confidence in knowing yourself “through and through” your unswerving commitment, “your higher strivings,” to improving yourself in the excellent works of the old masters.

The vulgar, the average and commonplace is always content with what is glaringly mediocre and downright mundane, and any grueling ascension to the realm of the divine and beautiful is often laughed-at and mocked as self-unconscious “snobbishness” or snootiness. But as the old saying goes: to every dog a suitable tail.

It is to be noticed that any sincere efforts to perfection (higher strivings) has always been met with resistance, mockery, envy, downright aspersion and persecution.

To be “well-liked,” it is often at the price of you having to “lower yourself with what is downright vulgar” and commonplace. This is the earthly plateau for those dear folks, bird of cheap plumage, completely devoid of eyes and ears and hearts for the simplest things of life.

Retrospectively, I have added some additional notes on landscape painting. These observations cannot be said to be completely objective, or “unerring” in what one could claim to be but my own one-sided interpretations of Maxfield Parrish’s remarkable technique.

For many years, American artist Maxfield Parrish was my true inspiration. I read everything I could find about his amazing technique, dazzling landscapes, and later, I tried to emulate his painting methods, especially his beautiful rocks, skies, peaceful streams and gnarled trees.

From 2000-2005, I spent countless days interpreting reality through the busy eyes of former artists. Art, more than music or religion, has provided me with a magical world less filled with sadness, woes and tragedies.

I first heard of Maxfield Parrish while studying at the Art Students League. The small school contains a bulky collection of time-stricken books dating back to nineteenth century!

It was a heavenly experience for me. I felt transported to the New York of the nineteenth century, and some old timers had vivid memories of Norman Rockwell eating at the cafeteria of the Art Students League.

For hours, I would immerse myself reading about the old American landscapes artists: Frederick Church, Thomas Cole, Maxfield Parish, among others. Since I lived a few blocks from the Hudson River, I always felt connected to the artists of the Hudson River School (nineteenth century).

In the year 2000, the Brooklyn Museum held an exhibition of Maxfield Parrish's oeuvre! It was one of the most uplifting memorable experiences of my life!

For the first time, I could see every detail in the hyper-realistic mind of Maxfield Parrish! I later learned that the master used augmented glasses to painting every leaf and twig of his lovely trees and foliage.

Such realism led Maxfield Parrish to believe that only God could paint a tree better than him. Well, I made up my to paint like him, and it took me three years to finally stop painting leaves in one of my lush landscapes. Find the image below, and then zoom-in with your mobile device.

Salvador Dalí and Maxfield Parrish, however differing in styles and genres, have both much in common: the gorgeous application of transparent colors through glazing!

True, since age 30, I have been fascinated by Parrish’s fantastical application of pure colors, but I would say that any technique, however great, may suffer setbacks, and all we could do is to be content with the results, alas, always wishing that things could have been bettered by more plausible methods.

Maxfield Parrish’s landscapes, however dazzling and luminous, may seem overworked or “dry,” but some of his landscapes are indeed stunning, mesmerizing and beautiful. Just take a look at his golden hues and yellows.

Daybreak by Maxfield Parrish!

This may explain why the best artists are, first and foremost, writers in their own right, for it is quite a daunting task to retain as much information and data without keeping records, diaries and carefully-dated materials of our painstaking trials and errors.

Great minds, such as Goethe, Alexander Von Humboldt, Leonardo da Vinci, A. Schopenhauer, Salvador Dali, Edward Gibbon, among the best thinkers of all times, owed their remarkable erudition to the accumulation of tomes of books: from the oldest literatures to the most wonderful books by contemporary authors.

Boxes upon boxes, drawers and closets are stuffed with manuscripts, scores of papers, carefully-numbered pages and writings, galore, may resume the long labors and toils of decades, which, after all, are the best trophies and harvest in the dusk of our lives.

Such books, if they are indeed great, may become part of our systematic approach to the complex problems and conundrums of existence. Like an artist, one is tasked to finding a little corner, a little studio, fire-proof, from which he-she may attempt to paint, either in words or ideas, the multicolored, multifarious canvas of our lives.

If such an artist is successful, then, he may then become a blessed child of beatitudes, the main problems of existence, ennui (boredom and sensual pleasures) would not beset him.

The Kingdom of God is Within You

Henry D. Thoreau, in the Walden Pond, assures us that he had never been bored. But if he such a person is only a great writer, such as Albert Camus, but not an artist, then the absurdity of existence would be the more glaringly obvious and unbearable, for he-she, lacking the blessed eyes of an artist, a saint, or a platonic philosopher, cannot rise to the realm of the divine and beautiful.

The higher spheres of Pythagoras are inaccesible for such a mortal, for he-she is neither intent on reaching the stars and skies of beauty, nor in enjoying the most spectacular landscapes and marvels as yet waiting for curious wanderers, wayfarers and pilgrims.

Such a person’s mind is bound to remain enchained with the shackles of things transient and fleeting. But for the artist, consecrated to his art with the devotion of a saint, life’s short span is not enough for all the great moments under the heaven of constant creativeness and productivity.

Of course, the art of living, vita beata, would demand a propitious hiatus from us, which the more intelligent ones, would gladly while-away in the nourishment of our intellectual faculties, or in the careful organization of our accumulated knowledge. For such a blessed human being, the avid reader, leisure is but a blissful moment with the higher pleasures of the mind: great books, prayers, meditation, classical music!

Foxed books beautifully saved in the shelves of yore are often the time-stricken records of sages and geniuses.

This is the main reason why I would compare an artist to a punctilious scribe, for like Leonardo da Vinci, who taught himself how to paint the subtlest secrets of light, shadow, tonality and color-application, one has to have an inner proclivity to being both a careful observer of all the phenomena of Mother Nature, a diligent writer, in equal terms, a marvelous scholar and an autodidact of great rigor and discipline without losing the freedom, fanciness and spontaneity of an artist.

True! For the most part, we own our improvement to the indispensable thoughts of great minds. Behind every artist there is always an inspiration, a master, and this is the golden secret behind greatness. Therefore, from the outset, choose the lives and biographies of the most excellent men and women.

Learn from their errors and mistakes, inquire on their trials and hardships, and from such failures and persecutions, go on to forge your inner-self anew, stronger and able to see clearly through the pervasive “gaslighting of your detractors.”

Overcome the World!

Like Christ, hold your wit firmly in what you already know to be part of your own experiences, part of your own treasure-trove, and when others try to cast doubts and questions in your talents, simply trust your silent inner scribe.

One cannot be too careful when spilling our thoughts through hasty writings or scribbles. A speedy hand is prone to err. May I find grace with those whose eyes and mind are but reflecting mirrors to superior works of arts and literature.

Most humbly, I felt compelled to correcting some petty trifles, lest my reader blame me of unwitting negligence and presumptuousness. Higher strivings may require the humility of a cobbler, or the long-wanderings of a pilgrim. But for a noble soul, be she or he a mere peasant or a prominent patrician, the things from above are always for the few (Check out Philippians Chapter 4:08)

But even if you are modest enough to seeking the simple things of this life, and would even build your cabin next to Thoreau, the noisy winds of the world and its vanities could rob you of the best moments and seasons.

Some would even cast doubts on your sanity, and may even declare you ripe for a madhouse. But here lies your strength, your confidence in knowing yourself “through and through” your unswerving commitment, “your higher strivings,” to improving yourself in the excellent works of the old masters.

The vulgar, the average and commonplace is always content with what is glaringly mediocre and downright mundane, and any grueling ascension to the realm of the divine and beautiful is often laughed-at and mocked as self-unconscious “snobbishness” or snootiness. But as the old saying goes: to every dog a suitable tail.

It is to be noticed that any sincere efforts to perfection (higher strivings) has always been met with resistance, mockery, envy, downright aspersion and persecution.

To be “well-liked,” it is often at the price of you having to “lower yourself with what is downright vulgar” and commonplace. This is the earthly plateau for those dear folks, bird of cheap plumage, completely devoid of eyes and ears and hearts for the simplest things of life.

Retrospectively, I have added some additional notes on landscape painting. These observations cannot be said to be completely objective, or “unerring” in what one could claim to be but my own one-sided interpretations of Maxfield Parrish’s remarkable technique.

For many years, American artist Maxfield Parrish was my true inspiration. I read everything I could find about his amazing technique, dazzling landscapes, and later, I tried to emulate his painting methods, especially his beautiful rocks, skies, peaceful streams and gnarled trees.

From 2000-2005, I spent countless days interpreting reality through the busy eyes of former artists. Art, more than music or religion, has provided me with a magical world less filled with sadness, woes and tragedies.

I first heard of Maxfield Parrish while studying at the Art Students League. The small school contains a bulky collection of time-stricken books dating back to nineteenth century!

It was a heavenly experience for me. I felt transported to the New York of the nineteenth century, and some old timers had vivid memories of Norman Rockwell eating at the cafeteria of the Art Students League.

For hours, I would immerse myself reading about the old American landscapes artists: Frederick Church, Thomas Cole, Maxfield Parish, among others. Since I lived a few blocks from the Hudson River, I always felt connected to the artists of the Hudson River School (nineteenth century).

In the year 2000, the Brooklyn Museum held an exhibition of Maxfield Parrish's oeuvre! It was one of the most uplifting memorable experiences of my life!

For the first time, I could see every detail in the hyper-realistic mind of Maxfield Parrish! I later learned that the master used augmented glasses to painting every leaf and twig of his lovely trees and foliage.

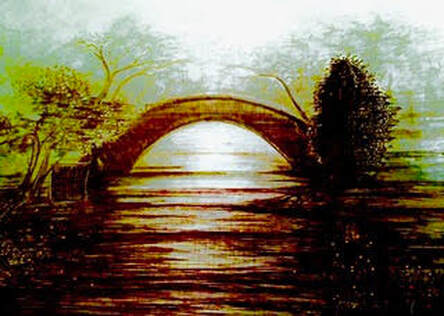

Such realism led Maxfield Parrish to believe that only God could paint a tree better than him. Well, I made up my to paint like him, and it took me three years to finally stop painting leaves in one of my lush landscapes. Find the image below, and then zoom-in with your mobile device.

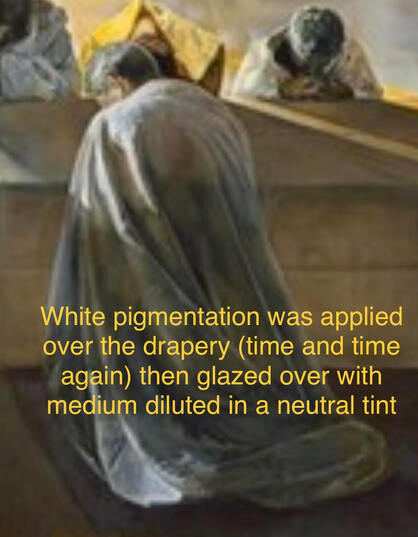

Salvador Dalí and Maxfield Parrish, however differing in styles and genres, have both much in common: the gorgeous application of transparent colors through glazing!

True, since age 30, I have been fascinated by Parrish’s fantastical application of pure colors, but I would say that any technique, however great, may suffer setbacks, and all we could do is to be content with the results, alas, always wishing that things could have been bettered by more plausible methods.

Maxfield Parrish’s landscapes, however dazzling and luminous, may seem overworked or “dry,” but some of his landscapes are indeed stunning, mesmerizing and beautiful. Just take a look at his golden hues and yellows.

Daybreak by Maxfield Parrish!

Nevertheless, few are those who would not botch a fine work of art through constant corrections, modifications and witless alterations, and even the best artists would make prowess but through “the painful path of trials and errors.”

The great challenge is to learn from our errors, and this is only possible by keeping track of our orderly-organized notes and years-long observations. Overtime you would master yourself in the careful study of your own experiences.

Keep your journals, keep a diary, keep your notebooks as references to your best performances and actions.

Become a person of the first order with the diligence of a scribe.

Once you have established your imprimatura, try not to upset the composition. The most beautiful paintings are those with little alteration of the underlying imprimatura.

Here lies the beauty of a flawless surface: shadows should be delicately transparent, and the lighter areas should be reserved for the highlights. If you start altering the composition, you may mar the cohesive wholeness and uniformity of the painting, and the magic of the underlying “white of the canvas” could be ruined by overworking or over-glazing.

Overgrazing could darken the local color-value, and you may end up creating a half-lit cave. Therefore, an area cast in darkness should not be overgrazed.

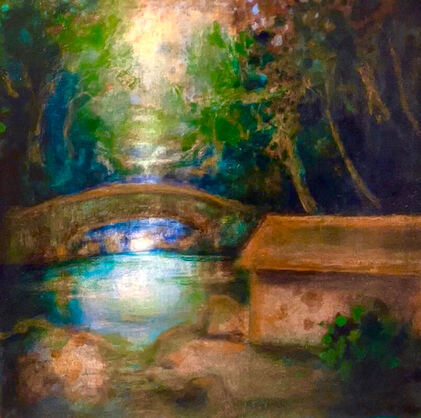

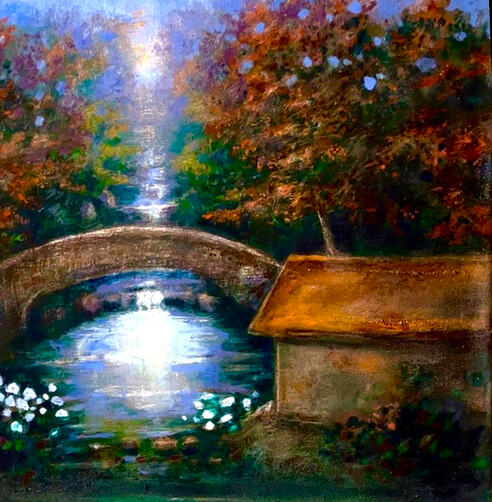

Imprimatura for Autumnal Cabin in the Wood.

The great challenge is to learn from our errors, and this is only possible by keeping track of our orderly-organized notes and years-long observations. Overtime you would master yourself in the careful study of your own experiences.

Keep your journals, keep a diary, keep your notebooks as references to your best performances and actions.

Become a person of the first order with the diligence of a scribe.

Once you have established your imprimatura, try not to upset the composition. The most beautiful paintings are those with little alteration of the underlying imprimatura.

Here lies the beauty of a flawless surface: shadows should be delicately transparent, and the lighter areas should be reserved for the highlights. If you start altering the composition, you may mar the cohesive wholeness and uniformity of the painting, and the magic of the underlying “white of the canvas” could be ruined by overworking or over-glazing.

Overgrazing could darken the local color-value, and you may end up creating a half-lit cave. Therefore, an area cast in darkness should not be overgrazed.

Imprimatura for Autumnal Cabin in the Wood.

Wake up early in the morning, and may you breathe the ambrosia of a great soul. Most importantly, do not lose heart when falling short to your high expectations. Better artists than you and I have left behind a plethora of unfinished projects and aspirations. Even Goethe, however a great writer, did not master the art of landscape painting.

Correcting errors may turn out to be a “serendipity.” Eureka! We all know that Mother Nature is often fond of erroneous paths and spontaneity, and there are things that cannot be learned through the rigor of scientific methods or any dint of rationality. Therefore, throw the dice, and see to your efforts the unpredictable blessings of Mother Nature.

Correcting errors may turn out to be a “serendipity.” Eureka! We all know that Mother Nature is often fond of erroneous paths and spontaneity, and there are things that cannot be learned through the rigor of scientific methods or any dint of rationality. Therefore, throw the dice, and see to your efforts the unpredictable blessings of Mother Nature.

Taking the challenge to painting like Maxfield Parrish could be a thankless task, and it would be rather “daring” to say one could emulate the technique of another artist, for like cooking, it is highly personal, in other words, —it is the signature of one’s personality. Therefore, every artist, in the words of Salvador Dali, has his-her own “cooking recipe.”

The Hudson River School Artists were known to contrive luminosity with broad washes of diluted paint (semi-transparent flake-white with a tint of blue, or + warm hues, yellowish and oranges), time and time again, thinly applied over the background.

Hence, the diluted tint should either be on the plus side (warm temperatures as conveyed by the effects of sunlights) usually yellow plus a little tint of crimson; or, in the minor (cold temperatures as tinged by the intervening bluish ether): flake-white which is not so opaque, with a tint of blue and crimson could create a convincing illusion of depth, ether and expansiveness.

Apply the diluted liquescent concoction over the background allowing details to show through. Wipe out any excess, and make sure shadows remain the strong bulwark for latter details. Flake-white could kill the strength of the color, but you can wipe out any excess with terpenoid or mineral spirit.

Hence, the diluted tint should either be on the plus side (warm temperatures as conveyed by the effects of sunlights) usually yellow plus a little tint of crimson; or, in the minor (cold temperatures as tinged by the intervening bluish ether): flake-white which is not so opaque, with a tint of blue and crimson could create a convincing illusion of depth, ether and expansiveness.

Apply the diluted liquescent concoction over the background allowing details to show through. Wipe out any excess, and make sure shadows remain the strong bulwark for latter details. Flake-white could kill the strength of the color, but you can wipe out any excess with terpenoid or mineral spirit.

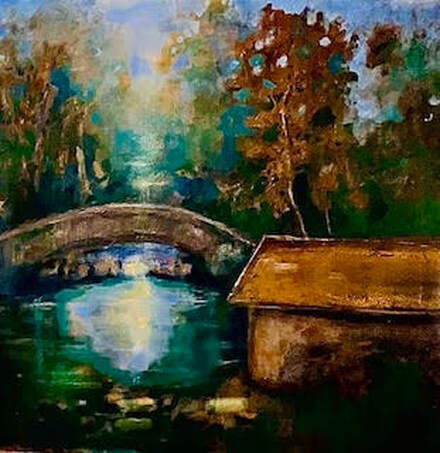

Notice the hazy sky and dark greens are congenially reflected in the streams: darker areas are the bed-ground for lighter foliages, but also serpentine organic tentacles, like those madly entangled tendrils, in their embattled will to exist, holding grasp jagged crags and cliffs, would all add to a wild world, pristine, and still under the sole domain of Mother Nature’s ever- blasting, uninterrupted, incessant creative potencies.

Upon the dark areas, I would block-in with fine details.

Painting a landscape is a thankless task, but a committed artist should never be satiated of Mother Nature’s amazing generosity.

Frederick Edwin Church rarely finished his paintings in two months. A View of Heart of the Andes, property of the Metropolitan Museum, could have easily taken from two to three years to the last final touches.

For sake of accuracy, F. Church would even take plants and samples of all kinds of foliages and rocks to build his own botanical garden. As a scientist-artist, he would then make color-studies and comparison of the said elements as perceived through the naked eye: hues, texture and shape.

Clouds may seem the easier stuff for an amateurish artist like myself, but receding mountains ranges, with their beautiful ethereal qualities, would require a fine teacher.

Painting foliage, shrubs and serried thickets a la Frederick Edwin Church, would require the patience of a saint, but painting every twig and leaf like Maxfield Parrish, would require an augmented glass and weeks of tedious repetitions.

Mind you that if you paint greens you would need browns and buff colors to make the scenery a pleasant harmonious whole!

If you wish to paint natural water or streams like F. Church, then you would need to study the illusion of reflecting elements in a pellucid surface, such as lakes, glens or ponds, and still, this may not be enough, there is this puzzle of transparency and “glaucous qualities” in the depth of some rivers and streams which may be more than just the simple reflections of skies and flora, or any other objects reflected therein.

At times, it seems as though F. Church’s depiction of water flowing was captured by an elusive scheme of colorless or neutral hues, indeed defying our understanding of the three primary colors: blue, red and yellow.

Therefore, if you have the patience of a saint, continue painting branches, leaves, twigs, shrubs, and splinters, galore, till the foreground has its full-fill of gladness.

Upon the dark areas, I would block-in with fine details.

Painting a landscape is a thankless task, but a committed artist should never be satiated of Mother Nature’s amazing generosity.

Frederick Edwin Church rarely finished his paintings in two months. A View of Heart of the Andes, property of the Metropolitan Museum, could have easily taken from two to three years to the last final touches.

For sake of accuracy, F. Church would even take plants and samples of all kinds of foliages and rocks to build his own botanical garden. As a scientist-artist, he would then make color-studies and comparison of the said elements as perceived through the naked eye: hues, texture and shape.

Clouds may seem the easier stuff for an amateurish artist like myself, but receding mountains ranges, with their beautiful ethereal qualities, would require a fine teacher.

Painting foliage, shrubs and serried thickets a la Frederick Edwin Church, would require the patience of a saint, but painting every twig and leaf like Maxfield Parrish, would require an augmented glass and weeks of tedious repetitions.

Mind you that if you paint greens you would need browns and buff colors to make the scenery a pleasant harmonious whole!

If you wish to paint natural water or streams like F. Church, then you would need to study the illusion of reflecting elements in a pellucid surface, such as lakes, glens or ponds, and still, this may not be enough, there is this puzzle of transparency and “glaucous qualities” in the depth of some rivers and streams which may be more than just the simple reflections of skies and flora, or any other objects reflected therein.

At times, it seems as though F. Church’s depiction of water flowing was captured by an elusive scheme of colorless or neutral hues, indeed defying our understanding of the three primary colors: blue, red and yellow.

Therefore, if you have the patience of a saint, continue painting branches, leaves, twigs, shrubs, and splinters, galore, till the foreground has its full-fill of gladness.

It would be ideal to arrange the flora like an unfolding row of successive things, one after the other, in tandem, and it should enhance the illusion of aerial perspective.

Once dried, with a tiny brush, completely drenched in oil medium (like Maxfield Parrish, zoom-in with an augmented glass) repaint tree’s autumnal leaves, however receding, work on stemming twigs and fork-tapering splinters against the transparent wash of flake-white plus a tint of ultramarine blue.

Little by little, contrive to interposing and interlacing branches, splinters, leaves and bushes, in tandem, coming forward to the foreground. Keep in mind the three planes: foreground, middle-ground and background.”

Once dried, with a tiny brush, completely drenched in oil medium (like Maxfield Parrish, zoom-in with an augmented glass) repaint tree’s autumnal leaves, however receding, work on stemming twigs and fork-tapering splinters against the transparent wash of flake-white plus a tint of ultramarine blue.

Little by little, contrive to interposing and interlacing branches, splinters, leaves and bushes, in tandem, coming forward to the foreground. Keep in mind the three planes: foreground, middle-ground and background.”

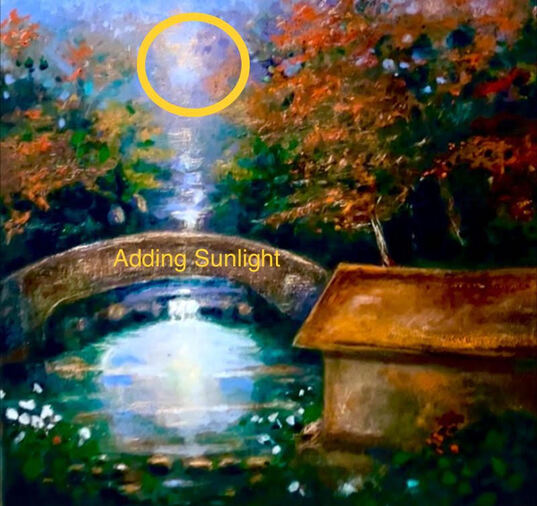

Adding Sunlight: painting a gentle sunlight bathing the background would enliven the painting to a felicitous new dawn: 2023!

Up to this point, thank you for bearing with me, but I had to continue working on “irregularities” and the interposing leaves and branches, in tandem, so as to “further enhance the illusion of perspective.”

Up to this point, thank you for bearing with me, but I had to continue working on “irregularities” and the interposing leaves and branches, in tandem, so as to “further enhance the illusion of perspective.”

Before I added the gentle sunlight, I contrived for “cools hues vs warm hues” in the receding ethereal background.

Sunlight cutting through the woods could further increase our sense of well-being and elation. Therefore, try to contrive the highest point or “acme” in your landscape paintings.

Sunlight cutting through the woods could further increase our sense of well-being and elation. Therefore, try to contrive the highest point or “acme” in your landscape paintings.

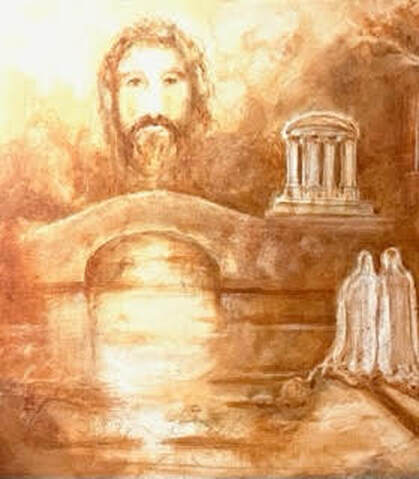

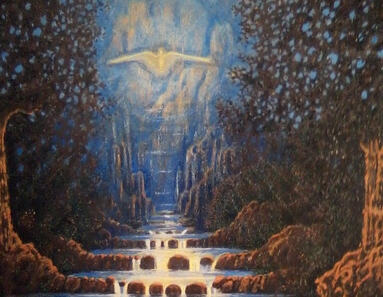

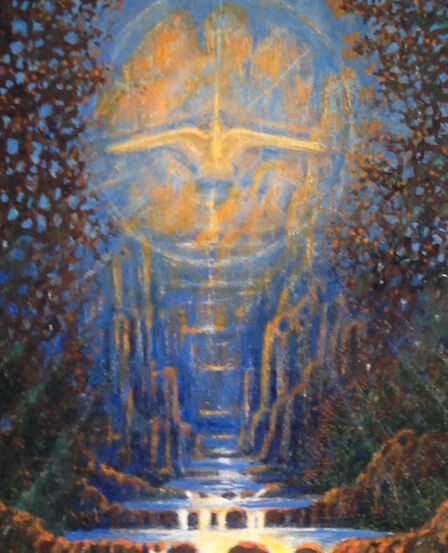

My Diary, January 2nd, 2023: Today I worked on the imprimatura of Back to Ancient Greece.

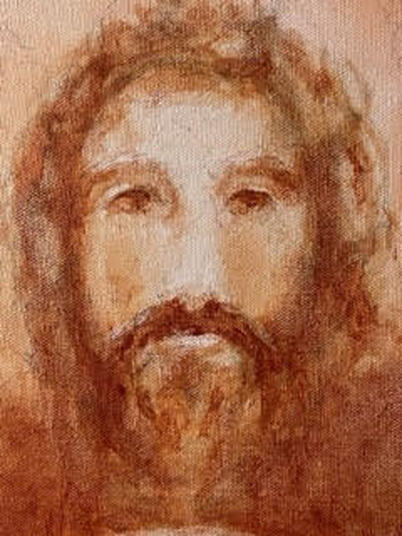

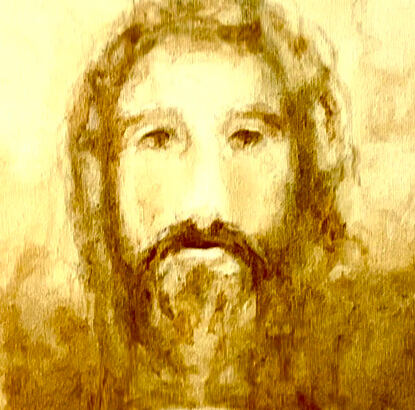

I behooves me to change the deities of yore for the new refreshing pastures and saints of Christianity. Accordingly, I tried to lend the face of Jesus an uncanny Greco-Roman visage as opposed to those Anglo-looking Jesus so common in most religious paintings and movies. No one has seen the face of Jesus, therefore, any realistic depiction would only lessen the “mysteriousness” of His Glory.

In the same train of thoughts concerning things divine and sublime, I would like to touch upon the Ancient Greeks and the quasi-pigment-less technique of Salvador Dali on the positive space: things and subjects coming forward to the viewer.

Once I have completed the imprimatura, I would sprinkle certain areas (especially the highlights) with Clorox Tilex to removing any unwanted stains or residues from the underlying pencil drawing.

I behooves me to change the deities of yore for the new refreshing pastures and saints of Christianity. Accordingly, I tried to lend the face of Jesus an uncanny Greco-Roman visage as opposed to those Anglo-looking Jesus so common in most religious paintings and movies. No one has seen the face of Jesus, therefore, any realistic depiction would only lessen the “mysteriousness” of His Glory.

In the same train of thoughts concerning things divine and sublime, I would like to touch upon the Ancient Greeks and the quasi-pigment-less technique of Salvador Dali on the positive space: things and subjects coming forward to the viewer.

Once I have completed the imprimatura, I would sprinkle certain areas (especially the highlights) with Clorox Tilex to removing any unwanted stains or residues from the underlying pencil drawing.

Let Clorox Tilex sink-in for a few minutes into the canvas, just enough time to removing the unwanted stains in areas losing the so-much-desired “sparkling highlights.”

Then, go on to sprinkle clean holy water over the canvas, and wash it clean to your heart’s content.

The results would be alike beautiful and marvelous —greater irregularities and a sparkling surface!

Such irregularities could not be achieved by the fanciest ingenuity of human imagination, or the artful skillfulness of human hands.

Such irregularities are produced by the sparkling drops as they evaporate into thin air, leaving behind their vaporous characters in a most agreeable although abstract semblance of the Face of Christ.

Then, go on to sprinkle clean holy water over the canvas, and wash it clean to your heart’s content.

The results would be alike beautiful and marvelous —greater irregularities and a sparkling surface!

Such irregularities could not be achieved by the fanciest ingenuity of human imagination, or the artful skillfulness of human hands.

Such irregularities are produced by the sparkling drops as they evaporate into thin air, leaving behind their vaporous characters in a most agreeable although abstract semblance of the Face of Christ.

Back to Ancient Greece:

My scene is taken from the last lines of Paradise, the Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri.

This is a Study On Cools Over A Warm Imprimatura:

My scene is taken from the last lines of Paradise, the Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri.

This is a Study On Cools Over A Warm Imprimatura:

For my version of the face of Jesus, I have studied the facial features of gods, deities and divinities from the astonishing imagination of ancient Greek artists!

We Christians have long abandoned any such imitations as the handiworks of devils and fallen angels, but aesthetically speaking, few cultures and peoples, if any, have ever surpassed the Children of Aurora in their monumental fireworks and numinous artistry.

Father Zeus is today deemed a pagan god, but when it comes to the ideas of things awesome and beautiful, the Ancient Greek artists, especially Phidias, had perhaps seen something divine in the abode of the gods: Mount Parnassus or Mount Olympus.

The face of a Divinity has to look somewhat serious and yet gentle, somber and yet majestic, serene and yet venerable, awesome and yet kind and reverent.

We Christians have long abandoned any such imitations as the handiworks of devils and fallen angels, but aesthetically speaking, few cultures and peoples, if any, have ever surpassed the Children of Aurora in their monumental fireworks and numinous artistry.

Father Zeus is today deemed a pagan god, but when it comes to the ideas of things awesome and beautiful, the Ancient Greek artists, especially Phidias, had perhaps seen something divine in the abode of the gods: Mount Parnassus or Mount Olympus.

The face of a Divinity has to look somewhat serious and yet gentle, somber and yet majestic, serene and yet venerable, awesome and yet kind and reverent.

Of course, the facial features ought to be left to the fancy of the beholder. Therefore, I would not make too much emphasis on realistic details.

Los rasgos característicos deben dejarse a la imaginación del espectador, porque cada quien lo verá de acuerdo a su interior.

La idea del físico o rostro de Jesús varía de cultura a cultura. Es muy posible que los antiguos, de acuerdo a sus ideas de lo sublime y majestuoso lo embellecieran con rasgos de la gente de Etiopía, los cuales Homero llamara “los niños de la aurora,” (the Iliad and the Odyssey).

Los rasgos característicos deben dejarse a la imaginación del espectador, porque cada quien lo verá de acuerdo a su interior.

La idea del físico o rostro de Jesús varía de cultura a cultura. Es muy posible que los antiguos, de acuerdo a sus ideas de lo sublime y majestuoso lo embellecieran con rasgos de la gente de Etiopía, los cuales Homero llamara “los niños de la aurora,” (the Iliad and the Odyssey).

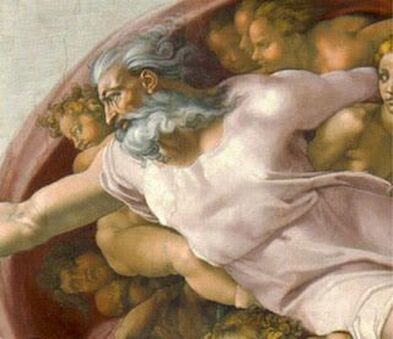

Si observas la versión del Dios de Miguelangel, es un hombre de Etiopía con tez de moreno Mediterráneo. En cambio, si observa la versión del Cristo de los Anglo, mas bien parece un actor de cine.

Likewise the depiction of Moises by the Rennaissance artist could convey an ineffable idea of a god-like human being. With greater glory, therefore, the face of Jesus ought to look no less glorious and magnificent than father Zeus.

Likewise the depiction of Moises by the Rennaissance artist could convey an ineffable idea of a god-like human being. With greater glory, therefore, the face of Jesus ought to look no less glorious and magnificent than father Zeus.

Glazing with Cool Colors Over a Warm Imprimatura:

Salvador Dalí pintada con muy poca “opacidad de pigmentos.” Sobre la imprimatura (primera capa con un color cálido) el solía aplicar colores fríos tales como el azul (con blanco). Este proceso lo hacía varias veces, aplicando un barniz entre las sucesivas capas.

Salvador Dalí pintada con muy poca “opacidad de pigmentos.” Sobre la imprimatura (primera capa con un color cálido) el solía aplicar colores fríos tales como el azul (con blanco). Este proceso lo hacía varias veces, aplicando un barniz entre las sucesivas capas.

You must google the word “scumbling” or scumble, because Salvador Dali was a master at both glazing and scumbling!

Dali seems to have scumbled (hard pressing of the brush with little blue+white paints) over the imprimatura to manipulating the “color temperature.” That he used rags, towel-papers and the likes to either applying or wiping off areas of paints is not to be discarded.

Painting the Landscape with Goethe's Theory of Colors

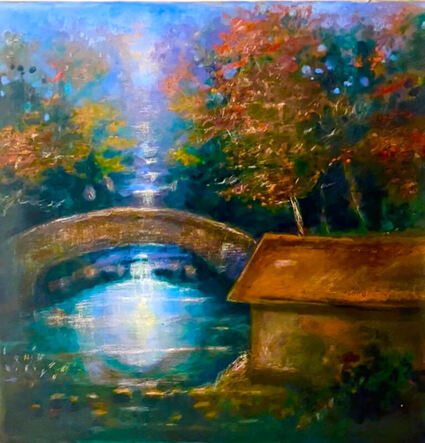

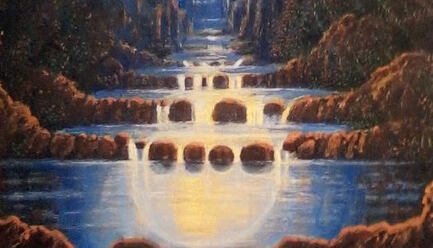

In this peaceful painting, an idealized Elysian view of the Central Park in New York City, I have embarked on an in-depth quest at closed square with the boons of Mother Nature.

I hope you find Peace, Inspiration and Love in these lush scenes, shortly-lived quiet moments of solitude, so redolent of the fragrant writings of Goethe and Henry D. Thoreau.

Bridge of Love with Eddie Beato

In this peaceful painting, an idealized Elysian view of the Central Park in New York City, I have embarked on an in-depth quest at closed square with the boons of Mother Nature.

I hope you find Peace, Inspiration and Love in these lush scenes, shortly-lived quiet moments of solitude, so redolent of the fragrant writings of Goethe and Henry D. Thoreau.

Bridge of Love with Eddie Beato

Some passages below are enclosed within asterisks (*) to indicate repetitions of previous passages while writing about Goethe's Landscape.

Let us first examine Goethe's basic painting technique, which, while lacking the mastery of landscapes artists the likes of Frederick Church or Thomas Cole, we may still reap the gleanings in some universal principles, i.e., "law of contrast and juxtaposition," which could be applied to any field of knowledge through the rigor of scientific observations, experiments, trials, errors and the propitious fruits of joy and peace in the seasoned harvest of the artist.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe gave up painting late in his life. He was better at drawing than at painting landscapes. One of his favorite landscape-painters was the Dutch painter Claude Lorraine.

Though late in his life, Goethe had learned the basic concepts (tools and methods) to creating a boundless sense of space, the "illusion of a tridimensional reality" --more so in some of his writings, which, by the way, are full-fraught with juxtapositions.

The great poet was Faust himself, even Werther in his strong artistic leanings and poetic reveries of incomparable depth and beauty as only possible to the most gifted minds.

Like his Faust, he lived a long life, and was able to school himself in many fields, including landscape painting, which he tried to master all his lifelong. Goethe died at the age of 82.

Landscape after the magic-mind of Goethe in contrasts and immeasurable depth:

Let us first examine Goethe's basic painting technique, which, while lacking the mastery of landscapes artists the likes of Frederick Church or Thomas Cole, we may still reap the gleanings in some universal principles, i.e., "law of contrast and juxtaposition," which could be applied to any field of knowledge through the rigor of scientific observations, experiments, trials, errors and the propitious fruits of joy and peace in the seasoned harvest of the artist.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe gave up painting late in his life. He was better at drawing than at painting landscapes. One of his favorite landscape-painters was the Dutch painter Claude Lorraine.

Though late in his life, Goethe had learned the basic concepts (tools and methods) to creating a boundless sense of space, the "illusion of a tridimensional reality" --more so in some of his writings, which, by the way, are full-fraught with juxtapositions.

The great poet was Faust himself, even Werther in his strong artistic leanings and poetic reveries of incomparable depth and beauty as only possible to the most gifted minds.

Like his Faust, he lived a long life, and was able to school himself in many fields, including landscape painting, which he tried to master all his lifelong. Goethe died at the age of 82.

Landscape after the magic-mind of Goethe in contrasts and immeasurable depth:

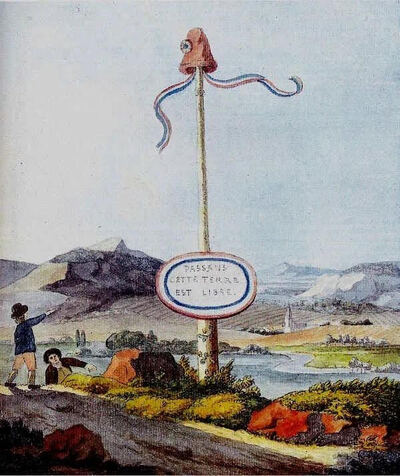

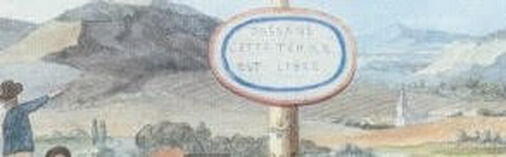

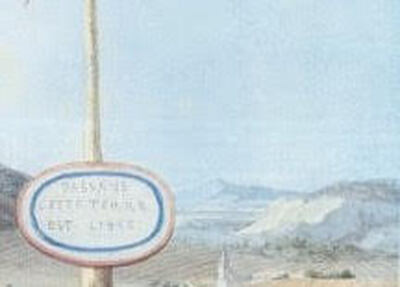

This is a remarkable water-color landscape due to aerial perspective, showing us a surprising understanding of tonal values (chroma and grand scheme of things) to capturing a convincing illusion of distance.

Color-Scheme For Distance: Value and Tones

*Foreground (high in chroma, contrast, sharp edges, value-range (from 2 to 8).*

Color-Scheme For Distance: Value and Tones

*Foreground (high in chroma, contrast, sharp edges, value-range (from 2 to 8).*

*Middle-ground (low in chroma, middle-value-range (from 3 to 5) and should not suffer from too much contrast or details.*

*Background: should not suffer from too much contrast, high-chroma, intensity, or sharp edges, but everything should blur gently and softly into the surrounding atmosphere).*

*High intensity in the background (as that of a blazing sun) would increase the contrast of values, and accordingly, stronger shadows and accents would be needed, thus requiring the extreme scheme of value-range: from 1 to 8, being the latter the lowest degree in darkness (foreground).*

The greatest contrasts would occur at the front-plane (the darkest value and the lightest brush-strokes).

Nevertheless, as we move towards the middle-ground, the scenery appears to be littered with rocks, hillocks, gully-like channels whereat a silvery, lovely river wounds itself amidst patches of lovely meadows and hills.

In the middle-ground, a church's spire or steeple rises up as though suggesting some far-reaching goal in views: perhaps there could be found the remnants of an abandoned temple, or perhaps these are the remaining ruins of former settlers in the hills of our strivings for an ideal existence.

Here, as we descry the haze of distance and its expansiveness, we would experience an elation, a buoyancy in the contemplation of our prospects in the pilgrimage of our lives.

The splendid scenery stretches far back into the haze of distance --like Homer's Odyssey, it recedes into the mist of a foggy past, remote, dreamlike, thus everything becomes less distinguishable and less marked by our selfish motives, concerns of the present or the future: the most common obvious accidents in the canvas of our peace and tranquility.

Like far-off mountain ranges -- assuming the delicacy of calm pastel shadings (mauvish), so we may experience an in-depth sense of wellbeing.*

The last blue mountain --like a lovely coin from the celestial mint of heaven's generosity, has a peculiar effect in my mind; there is "something of a soulful prospect" in indescribable longing for an idyllic past --a fine gift in knowing oneself in the distant spots!

Goethe's Water-Color Painting (background)

*High intensity in the background (as that of a blazing sun) would increase the contrast of values, and accordingly, stronger shadows and accents would be needed, thus requiring the extreme scheme of value-range: from 1 to 8, being the latter the lowest degree in darkness (foreground).*

The greatest contrasts would occur at the front-plane (the darkest value and the lightest brush-strokes).

Nevertheless, as we move towards the middle-ground, the scenery appears to be littered with rocks, hillocks, gully-like channels whereat a silvery, lovely river wounds itself amidst patches of lovely meadows and hills.

In the middle-ground, a church's spire or steeple rises up as though suggesting some far-reaching goal in views: perhaps there could be found the remnants of an abandoned temple, or perhaps these are the remaining ruins of former settlers in the hills of our strivings for an ideal existence.

Here, as we descry the haze of distance and its expansiveness, we would experience an elation, a buoyancy in the contemplation of our prospects in the pilgrimage of our lives.

The splendid scenery stretches far back into the haze of distance --like Homer's Odyssey, it recedes into the mist of a foggy past, remote, dreamlike, thus everything becomes less distinguishable and less marked by our selfish motives, concerns of the present or the future: the most common obvious accidents in the canvas of our peace and tranquility.

Like far-off mountain ranges -- assuming the delicacy of calm pastel shadings (mauvish), so we may experience an in-depth sense of wellbeing.*

The last blue mountain --like a lovely coin from the celestial mint of heaven's generosity, has a peculiar effect in my mind; there is "something of a soulful prospect" in indescribable longing for an idyllic past --a fine gift in knowing oneself in the distant spots!

Goethe's Water-Color Painting (background)

FOREGROUND:

Wise color-scheme by Goethe, because red-hues and yellow-hues tend to come forward to the viewer.

Wise color-scheme by Goethe, because red-hues and yellow-hues tend to come forward to the viewer.

The foreground, however cluttered and mottled with motley objects to catch our attention from the outset, is warmed-up with earth and ocher colors, thus tinging the fore-ground with higher saturation than the rather cool, silvery tones in the background.

Accordingly, gnarled rocks, trees, building or any other hard structures (angles, edges and rough surface and texture) would appear to suffer more from accidents, details, cutting-edge lines, shades, contrast, et. al. Thus, one is tasked to the painstaking labor of painting twigs, foliage, endless splinters, stems and a myriad of minutest things with the patience of a saint:

In the foreground, contrast, juxtaposition and range would reach the greatest degrees of light or darkness, of course, rarely reaching the 1 or 8 values (chiaroscuro).

Sharp Edges:

The foreground would have "sharp edges," and, unlike the background with soft edges, it is the most detailed area of all the planes in a landscape.

Accordingly, gnarled rocks, trees, building or any other hard structures (angles, edges and rough surface and texture) would appear to suffer more from accidents, details, cutting-edge lines, shades, contrast, et. al. Thus, one is tasked to the painstaking labor of painting twigs, foliage, endless splinters, stems and a myriad of minutest things with the patience of a saint:

In the foreground, contrast, juxtaposition and range would reach the greatest degrees of light or darkness, of course, rarely reaching the 1 or 8 values (chiaroscuro).

Sharp Edges:

The foreground would have "sharp edges," and, unlike the background with soft edges, it is the most detailed area of all the planes in a landscape.

Background (cold colors, soft edges, ethereal perspective)

Cool, silvery hues, bluish, grayer tones (weak in chroma and saturation) should be placed at the background (receding).

Cools and blueish colors tend to recede towards the background:

Take a look at the mountains' ranges and see and how they partake of the clean azure of the sky's cerulean blue!

*Making Objects Recede With A Coat of Milky Glaze Mixed With Transparent White:

Some artists would apply a coat of a transparent bluish layer (mixed

with a little bit transparent white diluted in medium) and would then carefully glaze objects in the background to make them blend, nay, recede farther into the distance. In this manner, the background would partake of an ethereal, all-permeating grisaille, which by contrast with the warm foreground, could create a very agreeable illusion of depth and atmospheric perspective.*

Cool, silvery hues, bluish, grayer tones (weak in chroma and saturation) should be placed at the background (receding).

Cools and blueish colors tend to recede towards the background:

Take a look at the mountains' ranges and see and how they partake of the clean azure of the sky's cerulean blue!

*Making Objects Recede With A Coat of Milky Glaze Mixed With Transparent White:

Some artists would apply a coat of a transparent bluish layer (mixed

with a little bit transparent white diluted in medium) and would then carefully glaze objects in the background to make them blend, nay, recede farther into the distance. In this manner, the background would partake of an ethereal, all-permeating grisaille, which by contrast with the warm foreground, could create a very agreeable illusion of depth and atmospheric perspective.*

Atmospheric Perspective:

As objects recede into the haze of distance, so they would soften in texture and weaken in intensity, and would even partake of the spectrum of the welkin (an all-encompassing bluish tint, or yellowish or orange light spectrum) casting everything with the same atmospheric light.

Seaport by Claude Lorraine

As objects recede into the haze of distance, so they would soften in texture and weaken in intensity, and would even partake of the spectrum of the welkin (an all-encompassing bluish tint, or yellowish or orange light spectrum) casting everything with the same atmospheric light.

Seaport by Claude Lorraine

(Note: It has been observed that the Odyssey of Homer is less bloody than the Iliad's chronicles with its endless horrendous slaughterings, dins, noise and many rambunctious people clashing for the sake of Helen's rosy cheeks).

By stark contrast, the latter stories of the Odyssey, like the distant blue mountains' ranges of Gothe's landscapes, seem to blur into another lost world of magic, a hazy distance, a dreamworld, which, before the invention of flying machines, such cheerful brushstrokes could have the far-off promise of something divine in the voyage of this brief existence.

Such is the lingering nostalgia that permeates Goethe and Thoureau in their sweet pastoral writings: a pilgrim-retreat back to the wilderness (Nature's broad-wayed paradises), which even for some-one like me living in the heart New York City with din and noise, this lost idyllic world --in spite of the cranking machine-- the hilly, precious memories of yore reververates within my soul's fabric with the profoundest significance: perhaps the poor soul could not know himself better, but in the blue contemplation of such hazy distance.

Opaque Pigments vs Transparent Ones

Sadly, Goethe, like Schopenhauer (peruse Parerga and Paralipomena vol. II, at the end of his fuddy-duddy essay On The Aesthetic of The Beautiful), the two philosophers, however busy in their careful observations of any visual ohenomena, had little understanding on the painting Methods of Van Eyck to achieving the fiery glare of colors as painted on a white canvas.

When it comes to writing, Goethe could contrive the greatest contrast possible (compare Phorcyas, the ugly woman, versus Helen the beautiful woman in Faust Part II), but in his painting methods and techniques, the great poet had not acheived the same mastery command of visual colors and forms at the brilliant level of Maxfield Parrish or Salvador Dali.

This should not be surprising, and it is not a matter of much disappointment to lessen the poet's tireless genius to the amateurish level of dilettantism. Latter painters learned to paint better landscapes but schooled in the immeasurable writings of Goethe.

Thanks to Goethe, and even though, the Pre-Raphaelite technique is not currently taught at The Art Student League, I had learned some secrets as to how to paint with transparent colors with vivid colors and contrasts from teachers at the aforementioned art school.

Let me insert this beautiful passage by Henry D. Thoreau at The Walden Pond, "Where I Lived, And What I lived For" (page 71):

"That way I looked between and over the near green hills to some distant and higher ones in the horizon, tinged with blue. Indeed, by standing at tiptoe I could catch a glimpse of some of the peaks of still bluer and more distant mountain ranges in the north-west, those true blue coins from heaven's own mint, but also a portion of the village.."

Life is extremely beautiful but it has to be appreciated it from the perspective of such poetic contemplations.

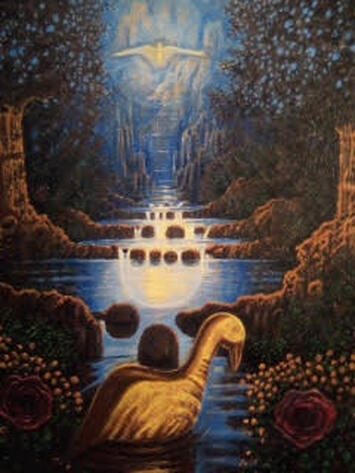

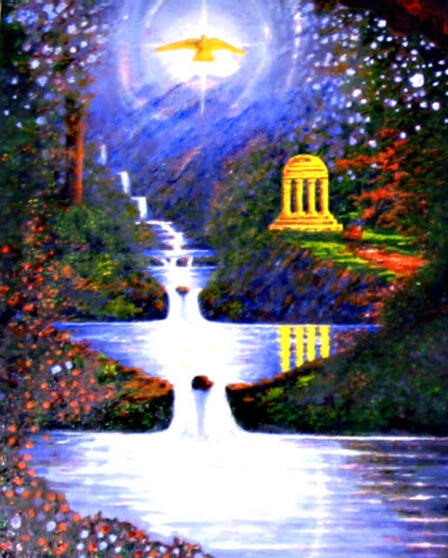

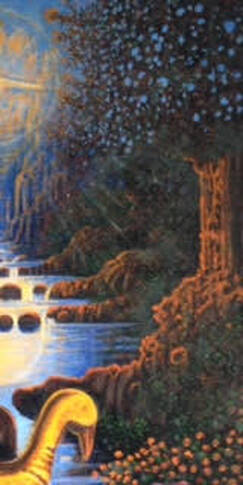

Painting the Garden of Eden

By Eddie Beato, New York City (Studies on the Pre-Raphaelite Technique, 2005-2008)

Colors-Scheme

Burn Umber

Alizarin Crimson

Cadmium Yellow

Titanium White

Esmeralda Green

Ultramarine Blue + a little bit of Cobalt Blue

The Imprimatura

A monochrome drawing of Burn Umber, or Burn Siena.

I used a technique similar to that used by Maxfield Parrish or Salvador Dali: pure colors scarcely mixed (or glazed) over a white canvas. Upon a white canvas, I would block-in with a warm color for my imprimatura:

By stark contrast, the latter stories of the Odyssey, like the distant blue mountains' ranges of Gothe's landscapes, seem to blur into another lost world of magic, a hazy distance, a dreamworld, which, before the invention of flying machines, such cheerful brushstrokes could have the far-off promise of something divine in the voyage of this brief existence.

Such is the lingering nostalgia that permeates Goethe and Thoureau in their sweet pastoral writings: a pilgrim-retreat back to the wilderness (Nature's broad-wayed paradises), which even for some-one like me living in the heart New York City with din and noise, this lost idyllic world --in spite of the cranking machine-- the hilly, precious memories of yore reververates within my soul's fabric with the profoundest significance: perhaps the poor soul could not know himself better, but in the blue contemplation of such hazy distance.

Opaque Pigments vs Transparent Ones

Sadly, Goethe, like Schopenhauer (peruse Parerga and Paralipomena vol. II, at the end of his fuddy-duddy essay On The Aesthetic of The Beautiful), the two philosophers, however busy in their careful observations of any visual ohenomena, had little understanding on the painting Methods of Van Eyck to achieving the fiery glare of colors as painted on a white canvas.

When it comes to writing, Goethe could contrive the greatest contrast possible (compare Phorcyas, the ugly woman, versus Helen the beautiful woman in Faust Part II), but in his painting methods and techniques, the great poet had not acheived the same mastery command of visual colors and forms at the brilliant level of Maxfield Parrish or Salvador Dali.

This should not be surprising, and it is not a matter of much disappointment to lessen the poet's tireless genius to the amateurish level of dilettantism. Latter painters learned to paint better landscapes but schooled in the immeasurable writings of Goethe.

Thanks to Goethe, and even though, the Pre-Raphaelite technique is not currently taught at The Art Student League, I had learned some secrets as to how to paint with transparent colors with vivid colors and contrasts from teachers at the aforementioned art school.

Let me insert this beautiful passage by Henry D. Thoreau at The Walden Pond, "Where I Lived, And What I lived For" (page 71):

"That way I looked between and over the near green hills to some distant and higher ones in the horizon, tinged with blue. Indeed, by standing at tiptoe I could catch a glimpse of some of the peaks of still bluer and more distant mountain ranges in the north-west, those true blue coins from heaven's own mint, but also a portion of the village.."

Life is extremely beautiful but it has to be appreciated it from the perspective of such poetic contemplations.

Painting the Garden of Eden

By Eddie Beato, New York City (Studies on the Pre-Raphaelite Technique, 2005-2008)

Colors-Scheme

Burn Umber

Alizarin Crimson

Cadmium Yellow

Titanium White

Esmeralda Green

Ultramarine Blue + a little bit of Cobalt Blue

The Imprimatura

A monochrome drawing of Burn Umber, or Burn Siena.

I used a technique similar to that used by Maxfield Parrish or Salvador Dali: pure colors scarcely mixed (or glazed) over a white canvas. Upon a white canvas, I would block-in with a warm color for my imprimatura:

You may compare the previews as sent to you back in December 2013, and how I contrived a cool background vs warm tints here and there.

A soft warm glow bathing the expansive bluish sky may further increase the glory, beauty and majesty of the abode of gods!

A soft warm glow bathing the expansive bluish sky may further increase the glory, beauty and majesty of the abode of gods!

Background: It is very likely that American artist, Frederick Edwin Church (The Hudson River School) would apply a broad-wash of warm hues (golden yellows and orange) in the background whereupon he would then paint his lovely blues and purples.

Washes of Cadmium Yellow + A Tint of Alizarin Crimson:

Washes of Cadmium Yellow + A Tint of Alizarin Crimson:

Painting lovely blues and purples over a warm wash of cadmium yellow + a tint alizarin crimson:

This is a fact of the retina (the eye), which seems to eke out for the complementary color. Hence, a lovely blue would require some tints of orange, yellow (purple), red (green).

The "White Foams" may relieve the eye of the strong reds and orange.

The "White Foams" may relieve the eye of the strong reds and orange.

If you place white next to orange, white would seem very delicate. There is a gentle stream of blue water in the background, thus bringing a pleasant calmness to the exciting tints of the autumnal leaves.

My favorite color is Blue!

Of course, I love rocks and gnarled trees with Buff or Reddish tints. White clouds are very lovely to look at, more wonderful when the Azure (pure Cerulean Blue) of a spacious sky paves your high-ways to infinity.

My favorite color is Blue!

Of course, I love rocks and gnarled trees with Buff or Reddish tints. White clouds are very lovely to look at, more wonderful when the Azure (pure Cerulean Blue) of a spacious sky paves your high-ways to infinity.

If you enjoy colors beyond the mere representational, then forget about realism, and start painting like a true abstract artist with good taste. It is a well known fact, colors and sounds affect your intelligence and awareness. Out of the three primary colors you may have countless combinations, imagine...:--).

The warm lovely crags and elating crevices for the distant mountains' ranges would act as underlying layers jutting out of the blue ranges.

The warm lovely crags and elating crevices for the distant mountains' ranges would act as underlying layers jutting out of the blue ranges.

Notice that I painted beetling rocks and crags, and all-through-out, I endeavored to convey the writings of John Milton (Paradise Lost) for a rough idea of a dream-like world still wild but beautiful: gnarled trees and rocks that do not obey the laws of linear thinking.

Avoid Straight Lines:

Straight lines were applied simply to add a sense of balance with the viewer's frame of mind, and some dear friends have not been so pleased with my symmetrical silly flowers...and rightly so!

The decoration of two huge flowers budding in the front-ground seems to me a little childish for a serious artist.

Avoid Straight Lines:

Straight lines were applied simply to add a sense of balance with the viewer's frame of mind, and some dear friends have not been so pleased with my symmetrical silly flowers...and rightly so!

The decoration of two huge flowers budding in the front-ground seems to me a little childish for a serious artist.

My next steps would be to re-enforce (glazing) the warms with transparent layers of yellows and oranges hither and thither...

Painting Foliage and Thickets:

I would start early in the morning, and thus would complete one section of the painting in one sitting. I painted many tiny leaves, foliages, twigs and buds, so small, that I had to use an "augmented glass" so as to be able to see them blossoming with gladness! In the background, the leaves and flowers are so small, that they compete for space with the tiny pores of the canvas.

I would start early in the morning, and thus would complete one section of the painting in one sitting. I painted many tiny leaves, foliages, twigs and buds, so small, that I had to use an "augmented glass" so as to be able to see them blossoming with gladness! In the background, the leaves and flowers are so small, that they compete for space with the tiny pores of the canvas.

Complementary Colors, Goethe's Theory of Colors

Zoom-in and see the little details.

Zoom-in and see the little details.

For contrast and complementary colors, I tried to follow Goethe's keen observations on the nature of colors and how they seem to eke out their complementary colors (Elective Affinities...like souls would attract kindred souls): Green-Red, Yellow-Purple, Orange-Blue.

The color "White," properly speaking, could not be said to be a color. It would relieve the retina from any stress or extreme exertion (saturation). Black shadows are found on the foreground.

Every Bird represents a phase in our short lives: I am actually the quiet bird on the mailbox of Henry D. Thoreau --under the gnarled tree of fortitude, solitude and middle age. The soaring bird is actually the Phoenix Bird of Transcendentalism --mas alla de las contradiciones de la existencia.

This painting, like the composition "The Last Supper," has been in my private collection for years. I need to find some one, some one akin that could appreciate it, and perhaps the painting will find a special place in the heart of a Goethean soul.

Your Humble Servant,

Ed. Beato

The color "White," properly speaking, could not be said to be a color. It would relieve the retina from any stress or extreme exertion (saturation). Black shadows are found on the foreground.

Every Bird represents a phase in our short lives: I am actually the quiet bird on the mailbox of Henry D. Thoreau --under the gnarled tree of fortitude, solitude and middle age. The soaring bird is actually the Phoenix Bird of Transcendentalism --mas alla de las contradiciones de la existencia.

This painting, like the composition "The Last Supper," has been in my private collection for years. I need to find some one, some one akin that could appreciate it, and perhaps the painting will find a special place in the heart of a Goethean soul.

Your Humble Servant,

Ed. Beato